The Vietnam War stemmed from America’s efforts to contain the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. By 1954, the end of French colonial rule left Vietnam divided into a communist North and pro-West South.

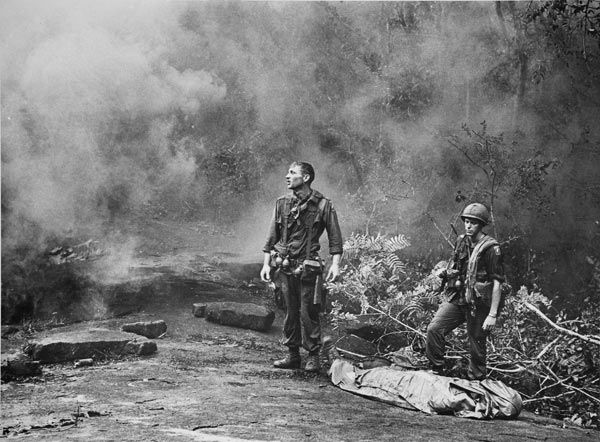

For the next several years, the United States supported South Vietnam with military advisors and then, by the mid-1960s, with ground troops. Young American men, many of them draftees, were deployed on year-long tours of duty in a protracted and increasingly bloody guerrilla war. By 1969, more than 550,000 Americans were serving in Southeast Asia.

As the fighting escalated, and casualties mounted, opposition to the war grew. Concerns about the fairness of the draft intensified, bringing about reforms, including a draft lottery.

Vowing “peace with honor,” President Richard M. Nixon began U.S. troop withdrawals but also widened the conflict with campaigns into Cambodia and Laos. Peace talks started in 1969 finally ended by 1973. American forces left and prisoners of war were repatriated. Two years later, the South fell to the communists.

By war’s end, 2.9 million Americans had served in the Vietnam theatre of operations. More than 58,000 were killed; some 300,000 had been wounded. The Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award for valor, was awarded to 246 soldiers who had served in Southeast Asia; 154 received this honor posthumously. An estimated three million Vietnamese across both sides perished during the conflict.